🛑 When Phaco Fails: Why Extracapsular Cataract Extraction (ECCE) is the Only Option for Mature Cataracts ✅

Executive Summary 💡

Phacoemulsification (Phaco) is the gold standard for most cataract surgeries. Surgeons celebrate it for its minimal incision and rapid recovery. However, its technological prowess faces a critical limit when confronting a dense, rock-hard, or “mature” cataract. This is the moment When Phaco Fails to deliver safe, predictable results. Crucially, using Phaco on such cataracts requires excessive ultrasonic energy. This results in a high risk of permanent corneal endothelial damage—the single most severe surgical complication. Therefore, Extracapsular Cataract Extraction (ECCE), particularly Manual Small Incision Cataract Surgery (MSICS), becomes the definitive, safer, and often only option. ECCE allows the surgeon to manually and gently remove the entire nucleus through a controlled incision. This method ensures the critical preservation of corneal health. Ultimately, the surgeon’s ability to choose ECCE over a failing Phaco attempt marks true surgical expertise, prioritizing the patient’s long-term visual integrity.

🌋 The Core Conflict: Why Phaco is Ill-Equipped for Hardness

Modern cataract surgery relies almost entirely on Phacoemulsification. This is a process where an ultrasonic probe fragments the lens nucleus into small pieces before aspiration. Nevertheless, this procedure is highly effective only up to a certain density. The challenge intensifies exponentially when the lens protein has hardened over years. This leads to a mature or hyper-mature cataract. This type of cataract presents an immediate technical paradox to the Phaco machine.

🧱 The Anatomy of a Mature Cataract: Brunescent and Nigra

The clinical density of a cataract is typically graded from 1 (soft) to 4 or 5 (rock-hard). Mature cataracts, known as brunescent (dark brown) or nigra (black), represent the highest end of this spectrum. These dark colors signify extensive protein oxidation and hardening. Importantly, the nucleus in these cases behaves less like soft tissue and more like solid stone. This presents a physical challenge that micro-incision surgery simply cannot overcome efficiently or safely. As a result, the procedure reaches a point When Phaco Fails to proceed without extreme intervention.

🔥 Phaco’s Fatal Flaw: Cumulative Dissipated Energy (CDE)

The Phaco probe generates Cumulative Dissipated Energy (CDE). This metric quantifies the total ultrasonic power and time used inside the eye. For a soft cataract, CDE remains minimal. Conversely, fragmenting a Grade 4 or 5 nucleus necessitates high power settings and extended time. This prolonged, intense energy release is the primary mechanism of danger. Therefore, surgeons meticulously monitor CDE. They know that exceeding a safe threshold jeopardizes the eye’s most vital layer. This threshold defines the limit When Phaco Fails to be a safe procedure.

Excessive CDE is not only a surgical risk but a severe threat to the long-term integrity of the eye. Dealing with high-energy procedures requires extreme precision. This precision is similar to that needed for complex treatments in other medical fields, such as robotic cancer surgery. In fact, surgical foresight and the willingness to pivot techniques define a world-class surgeon. They apply this wisdom whether performing a delicate eye procedure or a Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG).

⚠️ The Critical Danger Point: Irreversible Corneal Damage

The greatest immediate complication arising from high-CDE Phaco is damage to the corneal endothelium. The cornea, the clear front window of the eye, relies on this single layer of cells to remain transparent. Significantly, these cells do not regenerate in humans.

💧 Irreversible Damage: The Endothelium Cell Count

The endothelial cells act as pumps. They constantly push fluid out of the corneal stroma to prevent swelling (edema). Consequently, if a surgeon loses too many of these cells during a high-energy Phaco procedure, the cornea may become permanently swollen and opaque. This condition is called bullous keratopathy. In essence, the surgeon removes the cataract, but the patient loses their vision to corneal opacification. This necessitates a corneal transplant, which is a much more complex and risky procedure. Therefore, the surgeon often makes the decision to convert to ECCE preemptively. This avoids this tragic outcome. This confirms that for these dense cases, When Phaco Fails to safely manage CDE, ECCE is the ethical mandate.

⛓️ The Zonular and Capsular Weakness Factor

Mature cataracts often occur in older eyes. In these eyes, the delicate zonules—the microscopic fibers suspending the lens—may already be weak. This is a condition called zonulopathy. Moreover, the fluidic turbulence and mechanical stress inherent in Phaco are brutal on weak zonules. As a result, these fibers can rupture (zonular dialysis). This causes the lens or fragments to drop into the back of the eye (vitreous). This complication is another clear sign When Phaco Fails. It necessitates an immediate surgical conversion to ensure proper management and IOL placement.

🚩 Recognizing the Red Flags for Conversion

For the surgeon, the signs that Phaco is becoming unsafe are clear. The nucleus does not easily fragment, the eye chamber becomes turbulent, and the time spent emulsifying increases rapidly. Ultimately, delaying the conversion from Phaco to ECCE in this scenario turns a difficult but manageable case into a potential disaster. This crucial decision-making process is a testament to the comprehensive training received by surgeons. This is true in institutions worldwide, including those specializing in complex fields like neurosurgery or orthopedic medical tourism.

🛡️ ECCE: The Wise, Controlled Extraction (The Only Option)

Extracapsular Cataract Extraction (ECCE) is not an obsolete method. It is the ultimate tool for surgical safety in high-risk cases. Furthermore, many of the world’s leading ophthalmic surgeons maintain proficiency in ECCE. They do this precisely for these dense, mature cataracts. The technique involves creating a significantly larger incision, typically 8 to 12 mm. This incision allows the surgeon to manually express the entire, hardened nucleus in one piece.

🔬 Traditional ECCE vs. Modern MSICS

A linear incision in traditional ECCE requires the surgeon to meticulously close it with multiple sutures. This leads to a longer recovery and potentially greater induced astigmatism. However, modern practice has largely adopted its evolution: Manual Small Incision Cataract Surgery (MSICS). MSICS leverages the safety principle of ECCE (manual removal, zero ultrasound) but miniaturizes and optimizes the wound construction. This difference is key to understanding the superior results achieved today.

✨ The Superiority of MSICS Wound Architecture

The defining feature of MSICS is the meticulously constructed scleral tunnel. This tunnel uses the eye’s anatomy to create a wound that closes itself, much like a valve. Thus, this tunnel design allows for the manual extraction of the nucleus with minimal trauma. It often requires fewer or no sutures. Therefore, MSICS provides the CDE-free safety of ECCE while drastically reducing the recovery trade-offs. This makes it the technique of choice for high-volume surgeons dealing with advanced cataracts. This innovation is comparable to advancements in fertility enhancing surgeries or other precision medical procedures.

🤝 Pros and Cons: Comparing the Techniques for Mature Cataracts

✅ ECCE/MSICS Advantages (When Phaco Fails)

- Corneal Endothelium Safety: Zero ultrasonic energy eliminates the risk of CDE-induced damage.

- Controlled Extraction: Manual removal through a wide incision minimizes capsular and zonular stress.

- Stability in Trauma: Superior management of compromised capsules or weak zonules.

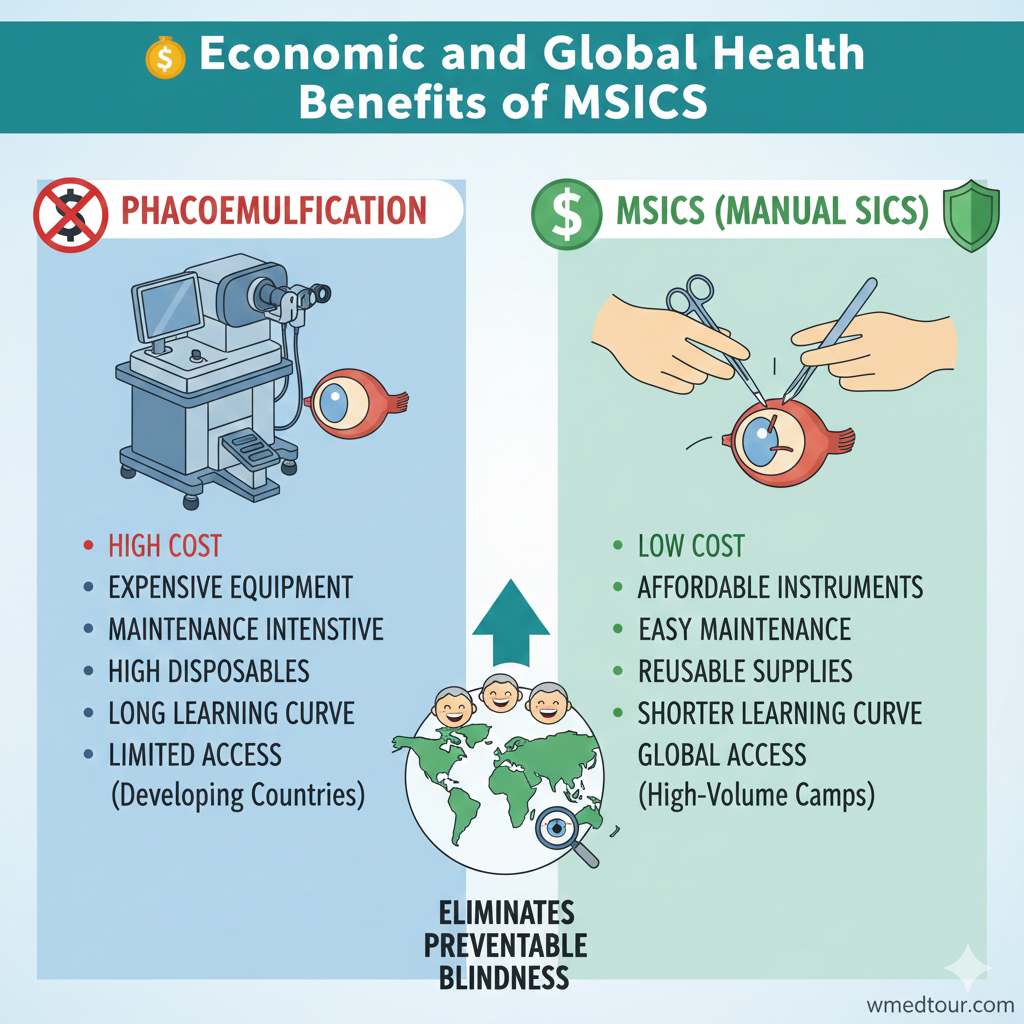

- Cost-Effectiveness: Lower equipment costs make it ideal for global health settings.

- Complete Nucleus Removal: Guaranteed removal of the rock-hard mass without leaving fragments.

❌ Phaco Limitations (On Mature Cataracts)

- High CDE Risk: Prolonged ultrasonic exposure guarantees endothelial cell loss.

- Zonular Stress: High fluidics and manipulation risk zonular rupture and lens drop.

- Micro-Incision Barrier: Difficulty managing the massive, non-fragmenting nucleus through a 2.8 mm port.

- Fragment Loss: High risk of nuclear fragments slipping into the posterior chamber.

- Potential for Conversion: An unplanned conversion carries higher risk than a primary ECCE.

🌍 MSICS: The Evolution of Safety and Global Imperative

The success of modern cataract surgery in managing the high volume of mature cataracts worldwide hinges largely on MSICS. Therefore, MSICS has become the flagship procedure in many medical tourism destinations known for high-volume, quality eye care. Patients seeking complex procedures like this often look for expertise in countries featured in our Global Medical Tourism Guide.

📐 MSICS Technique: Mastering the Self-Sealing Scleral Tunnel

The defining feature of MSICS is the meticulously constructed scleral tunnel. This tunnel uses the eye’s anatomy to create a wound that closes itself, much like a valve. Consequently, this tunnel minimizes post-operative leaking and infection risk. It also significantly reduces induced astigmatism. Hence, the surgeon can deliver the large nucleus without compromising the safety and integrity of the eye. This technical refinement is a major reason why MSICS is considered superior to older ECCE methods. It addresses the core technical failures of Phaco on mature lenses. The ability to perform this technique flawlessly is one of the key indicators of surgical quality. This is a standard we apply when vetting providers for procedures like choosing a surgeon abroad.

💰 Economic and Global Health Benefits of MSICS

ECCE, and MSICS in particular, are essential for global ophthalmology. The Phaco machine represents a massive initial investment. It requires frequent maintenance and depends on disposable components. In contrast, MSICS relies on simple, reusable instruments. It requires no high-tech machinery. Therefore, it is the most sustainable, high-volume, and affordable method for addressing the vast backlog of mature cataracts in resource-limited settings. Undeniably, MSICS proves that surgical wisdom and mastery, not just the latest technology, achieve the best outcome. This is especially true in cases where When Phaco Fails, it could lead to irreversible blindness. This is an important consideration when evaluating healthcare systems, such as those discussed in our Medical Travel Turkey Guide.

📊 Comparison Table: ECCE vs. Phaco for Mature Cataracts

This table summarizes why ECCE is not just an alternative. It is the imperative surgical choice for advanced cataract cases.

| Factor | Phacoemulsification (Phaco) | ECCE / MSICS (For Mature Cataracts) |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus Density (Grade 4-5) | High Risk / Often Fails | Optimal and Safe Indication |

| Corneal Endothelial Cell Loss | Significant (Due to high CDE and thermal stress) | Negligible (Zero ultrasonic energy used) |

| Incision Size | 2.2 – 2.8 mm (Micro-incision) | 5 – 12 mm (Macro-incision, often self-sealing MSICS) |

| Zonular Stress Risk | High (Due to fluidic turbulence and aspiration) | Low (Gentle, controlled, manual delivery) |

| Surgical Technique | Phaco-fragmentation and Aspiration | Manual Nucleus Expression (Hydro-expression) |

| Visual Rehabilitation Time | Fast (Days to weeks) | Moderate (Weeks to months, depending on sutures) |

🎯 Who is This For? Patient Profiles That Mandate ECCE/MSICS

The decision to perform ECCE is always based on the totality of the eye’s condition. It recognizes the heightened risk When Phaco Fails in complex scenarios. The requirement extends beyond just the hardness of the nucleus.

👁️🗨️ The High-Risk Patient Profile

The ideal candidates for ECCE/MSICS are those whose pre-operative diagnostics strongly suggest Phaco would be unsafe or incomplete. Firstly, any patient presenting with a visually dense, dark, Grade 4 or 5 cataract should be scheduled for MSICS. Secondly, patients with low pre-operative endothelial cell counts are poor candidates for the stress of Phaco. Indeed, preserving every cell is paramount in these eyes. This is a feat only ECCE can guarantee. Furthermore, certain corneal dystrophies or pre-existing swelling might preclude Phaco. Seeking a specialist who understands these nuances is critical for patient outcomes. Patients often travel for this specific expertise. Our guide to the Top Countries for ECCE Ophthalmology details this travel.

🩹 The Trauma and Complication History

ECCE offers superior mechanical control. This makes it essential for eyes with a history of trauma, previous eye surgeries (like vitrectomy or trabeculectomy), or known structural defects. For example, in eyes with small, fibrotic pupils that cannot be stretched or managed, the wider incision of ECCE provides the required operating space without inducing further injury. Moreover, eyes with confirmed zonular weakness (pseudoexfoliation syndrome) are inherently safer under the gentle manual extraction of ECCE. The controlled environment minimizes the risk of total capsular failure and vitreous loss, which Phaco fluidics often exacerbate. Similarly, patients who cannot remain still during the procedure, due to tremor or medical conditions, benefit from ECCE’s definitive, faster removal phase. This contrasts the prolonged emulsification time of Phaco. We understand that medical conditions can require complex care. We offer resources for related procedures like those in our Oncology Department and guidance for conditions like cystocele.

📚 Case Study: The Surgeon’s Wisdom in Conversion to MSICS

Patient Profile: Mr. Ahmed, Age 68 – Bilateral Cataracts

Mr. Ahmed, a 68-year-old traveling for specialized eye care, presented with cataracts planned for Phaco. His left eye, operated on first, was a successful, routine Phaco case with a Grade 2 nucleus. The team noted the right eye pre-operatively as a Grade 3, visually challenging case. The surgeon anticipated a difficult Phaco procedure but opted to start Phaco for the small incision benefit.

📉 The Moment When Phaco Fails

During the fragmentation phase on the right eye, the surgeon immediately noticed the nucleus was far harder than the Grade 3 pre-assessment suggested—closer to a Grade 4.5 brunescent cataract. Crucially, the probe could not effectively chop the nucleus. The CDE metric began climbing rapidly within the first 60 seconds. Moreover, the chamber became highly turbulent due to the required high vacuum and power settings. At this critical juncture, the surgeon correctly identified the unacceptably high risk of severe endothelial damage.

➡️ The Definitive ECCE Intervention

Without hesitation, the surgeon terminated the Phaco attempt and performed a controlled conversion to MSICS. This involved carefully extending the initial small incision to create a 6.5 mm self-sealing scleral tunnel. Using the MSICS technique, the surgeon successfully prolapsed the dense, intact nucleus into the anterior chamber. He then manually delivered it out of the eye. As a result, the surgeon completed the procedure safely with zero additional ultrasonic energy. While Mr. Ahmed’s recovery for the right eye was slower than the left, his final visual acuity and, more importantly, his corneal endothelial cell health were preserved. Ultimately, this decision exemplified the best surgical practice: knowing When Phaco Fails and having the skill to safely execute the alternative. This experience underscores the importance of choosing specialists. This is a key theme in our Best Ophthalmologist Guide.

🧐 Conclusion: Embracing Surgical Humility and Wisdom

We must frame the continuous debate between Phacoemulsification and Extracapsular Cataract Extraction. It is not a contest between old and new. It is a strategic decision based on the pathology of the eye. Indeed, for the vast majority of cataracts, Phaco is unsurpassed. However, for the dense, mature nucleus, ECCE (via modern MSICS) is the superior, safer, and necessary option. Therefore, a surgeon’s proficiency in both techniques, and the wisdom to know When Phaco Fails and when to convert, is the most crucial factor. This ensures the best outcome for the patient. Significantly, patients must ensure their chosen specialist is not only expert in Phaco but maintains impeccable skills in MSICS for these critical cases.

Ultimately, the goal of cataract surgery is clear vision without complication. For mature cataracts, ECCE is the most reliable path to achieving that goal. It eliminates the central risks of Phaco. We provide comprehensive resources to help patients prepare for such procedures, including our pre-travel resources and checklists.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about ECCE for Mature Cataracts

A mature cataract is characterized by a high-density, significantly hardened nucleus, often appearing brunescent (dark brown) or nigra (black). Phacoemulsification struggles to fragment this rock-hard nucleus without generating excessive heat and energy, which poses an unacceptable risk of permanent damage to the corneal endothelium, making ECCE the safer choice.

The corneal endothelium is a single, non-regenerating layer of cells crucial for maintaining corneal clarity. The extended use of ultrasonic energy (Cumulative Dissipated Energy or CDE) required to break up a mature nucleus during Phacoemulsification causes heat and mechanical trauma, which destroys these cells. ECCE avoids ultrasound entirely, ensuring the complete protection of the endothelium.

MSICS is a modern, highly refined variation of ECCE. While both involve manual, non-ultrasonic removal of the nucleus through a larger incision, MSICS uses a smaller (typically 5–7 mm), self-sealing scleral tunnel incision. This tunnel architecture significantly reduces the need for sutures, leading to faster stabilization of vision and lower post-operative astigmatism compared to traditional ECCE.

Absolutely not. An experienced surgeon converts from Phaco to ECCE (or MSICS) when pre-operative diagnostics underestimate the nucleus density, or when an intraoperative complication, like zonular weakness, is revealed. This conversion is a crucial, high-level skill that prioritizes patient safety and prevents catastrophic damage, confirming the surgeon’s wisdom and expertise. This is a sign of surgical excellence, much like successful complex procedures in our Orthopedic Surgery Department.

Recovery is generally longer with ECCE, primarily because the larger incision (for traditional ECCE) often requires sutures. The eye needs more time to heal, and final visual acuity can take several weeks or months to stabilize as the wound heals and sutures are adjusted or removed. MSICS recovery, however, is often much closer to Phaco recovery times.

The main risks include thermal burns at the incision site, irreversible loss of corneal endothelial cells due to CDE, and potential damage to the zonules (fibers holding the lens) from the fluidic turbulence, which could cause the lens or fragments to drop into the vitreous. The decision When Phaco Fails must be swift to mitigate these risks.

Yes, ECCE is often the preferred technique in eyes with small pupils (miosis) that resist dilation, or in cases where the pupil is scarred. The larger incision of ECCE provides superior visibility and access compared to the micro-incisions of Phaco, allowing the surgeon to safely maneuver and remove the dense nucleus.

ECCE and MSICS require minimal, simple, and durable equipment (basic microsurgery instruments). They do not rely on expensive Phaco machines and disposable supplies. This makes them highly cost-effective, sustainable, and the most reliable method for treating the vast number of neglected, mature cataracts found in resource-limited global settings. This is a key reason for medical travel to specialized centers, as covered in our Medical Travel Iran Visa Guide.

Both ECCE and Phaco are typically performed using local anesthesia (like a peribulbar or sub-Tenon’s block) supplemented by intravenous sedation. General anesthesia is rarely required, usually only for uncooperative patients, those with severe tremor, or complex pediatric cases.

Yes, the larger ECCE incision allows for the implantation of virtually any IOL, including foldable multifocal or toric lenses. However, since the eye’s shape (astigmatism) may take longer to stabilize due to the larger incision and sutures, the perfect calculation required for premium lenses can be more challenging. Therefore, careful pre-operative planning, which includes fertility screening for women, is essential, as detailed in our fertility treatments pre-travel checklist.

Zonular dialysis is the breakage or detachment of the zonules—the fibers that hold the lens in place. The turbulence and counter-pressure created by the Phaco machine can easily worsen this condition, leading to the lens dislocating. ECCE allows the surgeon to remove the lens gently and implant a specialized IOL with supporting devices, minimizing further zonular stress.

The MSICS technique creates a self-sealing, superiorly located scleral tunnel incision. Surgeons strategically place it to be far less disruptive to the corneal curvature than traditional ECCE. The ‘tunnel’ design minimizes wound gape. This results in significantly lower surgically induced astigmatism and contributes to faster visual recovery. This precision is comparable to advanced imaging for comprehensive health checkups.

Yes. If a surgeon anticipates a borderline high-density nucleus or has identified a high-risk factor, such as a low endothelial count, they may elect for primary ECCE/MSICS. Furthermore, this proactive decision is made to avoid all Phaco-related risks, guaranteeing the safest outcome. This approach is key to specialized treatment success, whether for ophthalmology or lung and thoracic surgery.

Yes. ECCE remains a vital skill that training programs teach to ophthalmology residents globally, particularly in programs focused on high-volume and resource-limited settings. Therefore, it is considered essential for handling complex cases and surgical complications that Phaco cannot address safely. Our network of doctors are often involved in such training.

Endothelial cell death means the permanent loss of the non-regenerating cell layer on the inner surface of the cornea. The shockwaves and heat generated by Phaco on a dense nucleus can cause this loss. Consequently, if the density is too high, When Phaco Fails to be gentle, the cornea swells irreversibly, leading to visual failure.

Yes. The large incision of ECCE is the reason why non-foldable, rigid Intraocular Lenses (IOLs) were historically used. These non-foldable lenses can sometimes offer superior stability in cases of marginal capsular support, which is often a secondary issue accompanying a mature cataract, a key consideration for specialists performing urological surgery or ophthalmology.

📚 Credible & Authoritative Resources

Authoritative References:

🔗 American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) – Cataract Surgery Techniques Comparison

🔗 JAMA Ophthalmology – Comparing Surgical Outcomes of MSICS vs. Phaco for Dense Cataracts

🔒 UCSF Health – When Phacoemulsification May Not Be Possible

🔒 National Library of Medicine (NIH) – Review on Corneal Endothelial Cell Loss in High-Grade Cataracts

Ophthalmology Department

affordable hip replacement surgery

Breast Augmentation Cost Iran 2025

Rhinoplasty Iran Price

global medical treatment regulations guide

Best Ophthalmologist Dubai

eye checkup ophthalmology checkup

ICCE cataract surgery

General Surgery

plastic surgery body

medical tourism iran

kidney transplantation

total knee replacement

fertility enhancing surgeries

cost vs quality robotic surgery

liver transplant surgery

bone marrow transplant bmt allogeneic

Hair Transplant Cost Turkey

contact us